Dakota McFadzean & Norma Dunning on Comics and Shorts

Dakota McFadzean & Norma Dunning on Comics and Shorts

1:01pm

Saturday, April 20, 2024

From plays to poetry, and novels to spoken word, the categories of storytelling are virtually endless. Each method uses unique literary devices to connect with readers and immerse them in the world the writer creates. To learn about two specific genres and the writers who bring them to life, the Toronto International Festival of Authors reached out to two authors of new short-form fiction for their insights on telling stories, the challenges of their chosen genre, and where they find their inspirations.

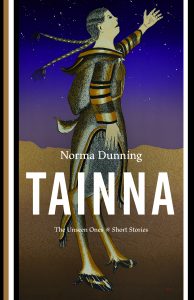

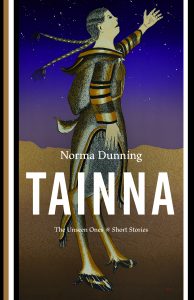

The following Q&A features Dakota McFadzean, a Canadian comic artist celebrating the release of his third book of comics, To Know You’re Alive, on May 27 as part of Toronto Lit Up; and Norma Dunning, an Inuit short story writer who released her second book, Tainna: The Unseen Ones, last month.

Can you tell us about your recently published book? Are there certain themes or situations that you explore through the stories?

Dakota McFadzean: To Know You’re Alive is a collection of short comics I made between 2013 and 2020. Most of the contents originally appeared in anthologies, lit magazines and self-published minicomics.

The stories in the first half of the book tend to be preoccupied with childhood and memory; either focusing on murky lines between real and imaginary, or exploring fictionalized versions of my own memories growing up in North Central Regina. The second half of the book consists of comics I made after becoming a father, and there’s a shift towards an outward-looking, adult point of view. There’s also an intermission that consists of comics that don’t really fit into either half.

The first half is a little somber and reflective, and the second half is more nightmarish. I might chalk that up to the sleeplessness of early parenting, but I think I also became a lot more afraid of the world after having kids.

Norma Dunning: Tainna: The Unseen Ones is exactly that. It is a collection of stories of the unseen, present-day Inuit peoples who are living outside of the tundra and who operate in modern-day life. It is a look at the hard truths, the explicit racism and the many ways that Inuit are harassed when as a people we are not living in the expected context of the north or standing at seal breathing holes with a harpoon in hand while wearing a fur-ringed parka.

How do your experiences impact your creative work?

Dakota McFadzean: Cartooning provides a lot of quiet, meditative time to sift through memories and reflect; I’ve always tended to be a little too nostalgic for my own good, so it was natural to use childhood memories as a starting point to explore ideas and images that are interesting to me. It can be rich territory because so much of childhood involves experiencing things for the first time.

Being a parent doesn’t leave a lot of time to daydream about the past, and so my attention has become much more focused on the present and future. I also started doing storyboarding work around that time. I was working on a board-driven show where each episode has an outline but no script, and it forced me to become a better writer. Or at least I became more comfortable with trying different things in my own writing.

Norma Dunning: My experiences are my creative work. What I have lived or observed from the lives of others is what I write. Every story contains a great deal of myself and the everyday accepted and expected discriminatory comments and gestures that I experience when I identify as an Inuk. Only Indigenous Canadians get held to the markers and measures of others.

What was it like publishing a book during the pandemic? Were there elements of the publishing process that changed because of it?

Dakota McFadzean: I wouldn’t recommend it if you have a choice. In terms of the actual process, I’m very fortunate to work in a field that involves a lot of social isolation to begin with, so the process translates well to a pandemic—it’s just me sitting at a computer preparing files to send to my publisher. I was working on this in the early months of the pandemic and, like many, the feeling that there might not be a future made it difficult for me to find the necessary energy to sit down and actually put the work in. I usually find a lot of satisfaction in the process of making comics and putting a book together, but during a pandemic that all seems hollow and trivial.

The lack of ability to actually promote the book in person in readings and events like The Toronto Comic Arts Festival is another big difference. I’ve been pleased with how the virtual promotion of this book has been going, but it would clearly be more fun and fulfilling to be in the same room as other people breathing the same air without a virus-related care in the world. Of course, that’s a minor problem in comparison to everything else that’s been lost in the last year.

Norma Dunning: As writers during a pandemic, I would think we all experienced delays from what was our expected launch dates.

Also, launching on Zoom is without human warmth because we are all posed on a laptop screen. Not being able to see an audience laugh or cry or hear applause at the end of each story creates a barrier for myself as the reader.

When you’re home alone and reading into a screen, the human element is missing.

What draws you to the genre? What do you enjoy most about it? What are some challenges?

Dakota McFadzean: I don’t usually set out to work in particular genres, but a number of the comics in this collection have elements of horror. I think I’ve often used comics to process feelings and ideas that are bothering me or are otherwise stuck in my mind. Plus creepy things are fun to draw.

I was really easily terrified by scary imagery when I was a kid. Even things like The Itchy & Scratchy Show on The Simpsons were way too frightening for me. I’d have these awful nightmares that would haunt me into the next day, and my dad would encourage me to draw them as a way of getting them out of my head. I’m not necessarily trying to do that with every comic I make, but it’s definitely a fundamental part of my relationship with drawing.

In terms of challenges, every story is different and I haven’t been interested in fully planting my feet in a particular genre, so the challenges are like spinning plates. Sometimes I’ll just have an image that I keep coming back to and try to build a story around it. Other times, the story flows out easily, but it’s not very interesting to draw. Cartooning can be such a slow, tedious process, and so I try to keep an element of spontaneity so that I’m more engaged with it.

Norma Dunning: I write as an older Inuk woman, therefore on the outside everything works against me. I’m old, I’m Indigenous and I am female, in theory I shouldn’t even be publishing!

What draws me is the need to make the global public think about Inuit and to give thought to the smallest Indigenous population in Canada who carry the highest rates in all the statistics that nobody else wants. The highest rates of teen suicide, the highest rates for food scarcity, the highest rates of over crowded housing—which all equal the highest rates of poverty.

What I have found is that as an Inuk writer if I couch our truth in fiction, people will take it in more readily and give it thought and to me that is what matters most.

Are there other genres of storytelling that you have tried or would like to try?

Dakota McFadzean: I’ve always liked science fiction, so I wouldn’t mind trying to work within that genre. There is an alien first contact story in this book, but it would be nice to work on a sci-fi story that’s longer and more involved.

Increasingly, I’m also attracted to the idea of doing pure all-ages comedy and seeing what I could do within those constraints. At the moment, I don’t know whether or not it’s a good idea to show my work to my kids.

Norma Dunning: No.

What makes a good story? How important is humour in connecting audiences to characters?

Dakota McFadzean: I’m not the right person to decide what makes a good story. The things I like and dislike about my own work are often so different from what readers respond to.

With each story, I try to keep surprising myself so that I can stay interested in drawing it for hours and hours. Sometimes the stories are made up as I go along with little planning, but even when I structure and plan everything ahead of time I still need to be able to make unexpected choices on the page as I’m drawing it. A different page layout, different pacing, different dialogue etc. I just try to work on it until it feels ‘right’ based on some abstract, imaginary parameters. There has to be room to play within the process.

As for humour, I love comedy and I love trying to be funny, but it’s not vital to every story. Forced or misplaced humour can detract from the story and character.

Norma Dunning: The writer knows when a story is good. They know it as they are writing it.

Humour is the one thing that connects us all, but most importantly it is all Indigenous Canadians’ greatest asset. Inuit, First Nations and Métis have been blessed with laughter and throughout our history and our present day disparities we have been and will continue to be able to laugh.

If what I am writing makes me laugh than I know it will make everyone laugh.

What is your creative process like? Do you have a dedicated workspace or routine?

Dakota McFadzean: Currently I’m a full-time stay-at-home dad. Well, a lot of people are stay-at-home right now, but I mean I’m with my two-year-old and, now that schools are closed, my five-year-old all day every day. There aren’t a lot of moments to even hold a thought in my head for more than three minutes, let alone have any kind of creative process.

I do have a small space that I rent in a shared studio, and when COVID numbers were low in Toronto, I would go there in the evenings just to work on comic strips and sketches. I’ve put any delusions of working on something more substantial on the back burner for now. On good days, I try to view this as a well-earned sabbatical and an opportunity to avoid creative burnout. On other days, I miss spending more time at the studio. But with the current infection numbers in Toronto, it’s not worth the risk of even going to the studio. Too many of the other artists do not wear masks, and I’m pretty sure a few of them think vaccines are a scam or that you can cure COVID with crystals or something.

When I’m not a stay-at-home parent and not living in a global pandemic, I like to work 9-5 in the studio. I do the more mentally taxing writing and pencilling work in the mornings when I’m feeling fresh, and inking and lettering in the afternoon while listening to podcasts or music. I used to continue working in the evenings too, but I’ve started to become increasingly protective of my down-time in the evenings

Norma Dunning: I don’t have a ‘process’ – who does? I work at least two jobs and when I have time I write.

Are there writers or creators within the genre whom you admire?

Dakota McFadzean: I recently listened to the audiobook of the Southern Reach Trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer, which is sci-fi and horror (an evergreen combination!) It was so different from the book’s movie adaptation, Annihilation, but I liked both a lot for different reasons. I feel like that’s a good example of how the same subject matter can be explored differently depending on the medium.

In terms of the medium of comics, there are certainly a number of cartoonists I admire, though not necessarily within the same genres. The work of Charles Schulz, Bill Watterson, and virtually anyone involved with MAD Magazine is what pulled me into comics in the first place, so I have a lifelong admiration for them. More contemporary examples might include Seth, Kevin Huizenga, Lynda Barry, Joe Ollmann, Eleanor Davis. There are too many to count.

Norma Dunning: Marilyn Dumont is my all time favourite poet and Richard Wagamese will always be my all time favourite prose writer.

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers and creators?

Dakota McFadzean: Be satisfied with just putting in the hours making the work and sharing it with others. Anything beyond that is not guaranteed, and might come down to luck and timing anyway. It’s not bad to have goals, or to network, or to strive for bigger opportunities, but if your happiness and self-worth hinge on fame and fortune you’re probably going to be miserable.

Being a cartoonist is kind of a ridiculous, ill-advised thing to do, so you’d best make peace with the process.

Norma Dunning: Don’t be afraid to publish! Don’t be like me and wait until you’re in the last third of life to let it rip—let it rip now!

About the Writers & Their Books:

Dakota McFadzean is a Canadian cartoonist who has been published by MAD Magazine, The New Yorker, The Best American Comics and Funny or Die. He has also worked as a storyboard artist for DreamWorks, and is an alumni of The Center for Cartoon Studies. To Know You’re Alive is McFadzean’s third book with Conundrum Press. Other titles include Other Stories and the Horse You Rode in On and Don’t Get Eaten by Anything, which collects three years of daily comic strips. McFadzean currently lives in Toronto with his wife and two sons.

To Know You’re Alive is a brilliantly dark collection that offers a glimpse into the cracks between childhood imagination and the disappointing harshness of adulthood. Populated by cruel bullies, exhausted parents and relentless cartoon mascots, McFadzean’s latest work renders the familiar into something that is alien and absurd. The characters in these stories long to uncover something uncanny in shadowy attics and beneath masks, only to discover that sometimes it’s worse to find nothing at all. Get your copy here.

Dr. Norma Dunning is a writer as well as a scholar, researcher, professor and grandmother. Her first book, the short story collection Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, received the Danuta Gleed Literary Award, the Howard O’Hagan Award for Short Story and the Bronze for short stories in the Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards. She is also the author of Eskimo Pie, a collection of poetry and an Alberta bestseller. Tainna: The Unseen Ones (Douglas & McIntyre) is an honouring to all Inuit who live outside of their land claims areas and who face modern-day life with humour and tenacity, and with the strength of the giants they are. Dunning lives in Edmonton, AB.

Drawing on both lived experience and cultural memory, Norma Dunning brings together six powerful new short stories centred on modern-day Inuk characters in Tainna. Ranging from homeless to extravagantly wealthy, from spiritual to jaded, young to elderly, and even from alive to deceased, Dunning’s characters are united by shared feelings of alienation, displacement and loneliness resulting from their experiences in southern Canada. There, they must rely on their wits, artistic talent, senses of humour and spirituality for survival; and there, too, they find solace in shining moments of reconnection with their families and communities. Get your copy here.

From plays to poetry, and novels to spoken word, the categories of storytelling are virtually endless. Each method uses unique literary devices to connect with readers and immerse them in the world the writer creates. To learn about two specific genres and the writers who bring them to life, the Toronto International Festival of Authors reached out to two authors of new short-form fiction for their insights on telling stories, the challenges of their chosen genre, and where they find their inspirations.

The following Q&A features Dakota McFadzean, a Canadian comic artist celebrating the release of his third book of comics, To Know You’re Alive, on May 27 as part of Toronto Lit Up; and Norma Dunning, an Inuit short story writer who released her second book, Tainna: The Unseen Ones, last month.

Can you tell us about your recently published book? Are there certain themes or situations that you explore through the stories?

Dakota McFadzean: To Know You’re Alive is a collection of short comics I made between 2013 and 2020. Most of the contents originally appeared in anthologies, lit magazines and self-published minicomics.

The stories in the first half of the book tend to be preoccupied with childhood and memory; either focusing on murky lines between real and imaginary, or exploring fictionalized versions of my own memories growing up in North Central Regina. The second half of the book consists of comics I made after becoming a father, and there’s a shift towards an outward-looking, adult point of view. There’s also an intermission that consists of comics that don’t really fit into either half.

The first half is a little somber and reflective, and the second half is more nightmarish. I might chalk that up to the sleeplessness of early parenting, but I think I also became a lot more afraid of the world after having kids.

Norma Dunning: Tainna: The Unseen Ones is exactly that. It is a collection of stories of the unseen, present-day Inuit peoples who are living outside of the tundra and who operate in modern-day life. It is a look at the hard truths, the explicit racism and the many ways that Inuit are harassed when as a people we are not living in the expected context of the north or standing at seal breathing holes with a harpoon in hand while wearing a fur-ringed parka.

How do your experiences impact your creative work?

Dakota McFadzean: Cartooning provides a lot of quiet, meditative time to sift through memories and reflect; I’ve always tended to be a little too nostalgic for my own good, so it was natural to use childhood memories as a starting point to explore ideas and images that are interesting to me. It can be rich territory because so much of childhood involves experiencing things for the first time.

Being a parent doesn’t leave a lot of time to daydream about the past, and so my attention has become much more focused on the present and future. I also started doing storyboarding work around that time. I was working on a board-driven show where each episode has an outline but no script, and it forced me to become a better writer. Or at least I became more comfortable with trying different things in my own writing.

Norma Dunning: My experiences are my creative work. What I have lived or observed from the lives of others is what I write. Every story contains a great deal of myself and the everyday accepted and expected discriminatory comments and gestures that I experience when I identify as an Inuk. Only Indigenous Canadians get held to the markers and measures of others.

What was it like publishing a book during the pandemic? Were there elements of the publishing process that changed because of it?

Dakota McFadzean: I wouldn’t recommend it if you have a choice. In terms of the actual process, I’m very fortunate to work in a field that involves a lot of social isolation to begin with, so the process translates well to a pandemic—it’s just me sitting at a computer preparing files to send to my publisher. I was working on this in the early months of the pandemic and, like many, the feeling that there might not be a future made it difficult for me to find the necessary energy to sit down and actually put the work in. I usually find a lot of satisfaction in the process of making comics and putting a book together, but during a pandemic that all seems hollow and trivial.

The lack of ability to actually promote the book in person in readings and events like The Toronto Comic Arts Festival is another big difference. I’ve been pleased with how the virtual promotion of this book has been going, but it would clearly be more fun and fulfilling to be in the same room as other people breathing the same air without a virus-related care in the world. Of course, that’s a minor problem in comparison to everything else that’s been lost in the last year.

Norma Dunning: As writers during a pandemic, I would think we all experienced delays from what was our expected launch dates.

Also, launching on Zoom is without human warmth because we are all posed on a laptop screen. Not being able to see an audience laugh or cry or hear applause at the end of each story creates a barrier for myself as the reader.

When you’re home alone and reading into a screen, the human element is missing.

What draws you to the genre? What do you enjoy most about it? What are some challenges?

Dakota McFadzean: I don’t usually set out to work in particular genres, but a number of the comics in this collection have elements of horror. I think I’ve often used comics to process feelings and ideas that are bothering me or are otherwise stuck in my mind. Plus creepy things are fun to draw.

I was really easily terrified by scary imagery when I was a kid. Even things like The Itchy & Scratchy Show on The Simpsons were way too frightening for me. I’d have these awful nightmares that would haunt me into the next day, and my dad would encourage me to draw them as a way of getting them out of my head. I’m not necessarily trying to do that with every comic I make, but it’s definitely a fundamental part of my relationship with drawing.

In terms of challenges, every story is different and I haven’t been interested in fully planting my feet in a particular genre, so the challenges are like spinning plates. Sometimes I’ll just have an image that I keep coming back to and try to build a story around it. Other times, the story flows out easily, but it’s not very interesting to draw. Cartooning can be such a slow, tedious process, and so I try to keep an element of spontaneity so that I’m more engaged with it.

Norma Dunning: I write as an older Inuk woman, therefore on the outside everything works against me. I’m old, I’m Indigenous and I am female, in theory I shouldn’t even be publishing!

What draws me is the need to make the global public think about Inuit and to give thought to the smallest Indigenous population in Canada who carry the highest rates in all the statistics that nobody else wants. The highest rates of teen suicide, the highest rates for food scarcity, the highest rates of over crowded housing—which all equal the highest rates of poverty.

What I have found is that as an Inuk writer if I couch our truth in fiction, people will take it in more readily and give it thought and to me that is what matters most.

Are there other genres of storytelling that you have tried or would like to try?

Dakota McFadzean: I’ve always liked science fiction, so I wouldn’t mind trying to work within that genre. There is an alien first contact story in this book, but it would be nice to work on a sci-fi story that’s longer and more involved.

Increasingly, I’m also attracted to the idea of doing pure all-ages comedy and seeing what I could do within those constraints. At the moment, I don’t know whether or not it’s a good idea to show my work to my kids.

Norma Dunning: No.

What makes a good story? How important is humour in connecting audiences to characters?

Dakota McFadzean: I’m not the right person to decide what makes a good story. The things I like and dislike about my own work are often so different from what readers respond to.

With each story, I try to keep surprising myself so that I can stay interested in drawing it for hours and hours. Sometimes the stories are made up as I go along with little planning, but even when I structure and plan everything ahead of time I still need to be able to make unexpected choices on the page as I’m drawing it. A different page layout, different pacing, different dialogue etc. I just try to work on it until it feels ‘right’ based on some abstract, imaginary parameters. There has to be room to play within the process.

As for humour, I love comedy and I love trying to be funny, but it’s not vital to every story. Forced or misplaced humour can detract from the story and character.

Norma Dunning: The writer knows when a story is good. They know it as they are writing it.

Humour is the one thing that connects us all, but most importantly it is all Indigenous Canadians’ greatest asset. Inuit, First Nations and Métis have been blessed with laughter and throughout our history and our present day disparities we have been and will continue to be able to laugh.

If what I am writing makes me laugh than I know it will make everyone laugh.

What is your creative process like? Do you have a dedicated workspace or routine?

Dakota McFadzean: Currently I’m a full-time stay-at-home dad. Well, a lot of people are stay-at-home right now, but I mean I’m with my two-year-old and, now that schools are closed, my five-year-old all day every day. There aren’t a lot of moments to even hold a thought in my head for more than three minutes, let alone have any kind of creative process.

I do have a small space that I rent in a shared studio, and when COVID numbers were low in Toronto, I would go there in the evenings just to work on comic strips and sketches. I’ve put any delusions of working on something more substantial on the back burner for now. On good days, I try to view this as a well-earned sabbatical and an opportunity to avoid creative burnout. On other days, I miss spending more time at the studio. But with the current infection numbers in Toronto, it’s not worth the risk of even going to the studio. Too many of the other artists do not wear masks, and I’m pretty sure a few of them think vaccines are a scam or that you can cure COVID with crystals or something.

When I’m not a stay-at-home parent and not living in a global pandemic, I like to work 9-5 in the studio. I do the more mentally taxing writing and pencilling work in the mornings when I’m feeling fresh, and inking and lettering in the afternoon while listening to podcasts or music. I used to continue working in the evenings too, but I’ve started to become increasingly protective of my down-time in the evenings

Norma Dunning: I don’t have a ‘process’ – who does? I work at least two jobs and when I have time I write.

Are there writers or creators within the genre whom you admire?

Dakota McFadzean: I recently listened to the audiobook of the Southern Reach Trilogy by Jeff VanderMeer, which is sci-fi and horror (an evergreen combination!) It was so different from the book’s movie adaptation, Annihilation, but I liked both a lot for different reasons. I feel like that’s a good example of how the same subject matter can be explored differently depending on the medium.

In terms of the medium of comics, there are certainly a number of cartoonists I admire, though not necessarily within the same genres. The work of Charles Schulz, Bill Watterson, and virtually anyone involved with MAD Magazine is what pulled me into comics in the first place, so I have a lifelong admiration for them. More contemporary examples might include Seth, Kevin Huizenga, Lynda Barry, Joe Ollmann, Eleanor Davis. There are too many to count.

Norma Dunning: Marilyn Dumont is my all time favourite poet and Richard Wagamese will always be my all time favourite prose writer.

Do you have any advice for aspiring writers and creators?

Dakota McFadzean: Be satisfied with just putting in the hours making the work and sharing it with others. Anything beyond that is not guaranteed, and might come down to luck and timing anyway. It’s not bad to have goals, or to network, or to strive for bigger opportunities, but if your happiness and self-worth hinge on fame and fortune you’re probably going to be miserable.

Being a cartoonist is kind of a ridiculous, ill-advised thing to do, so you’d best make peace with the process.

Norma Dunning: Don’t be afraid to publish! Don’t be like me and wait until you’re in the last third of life to let it rip—let it rip now!

About the Writers & Their Books:

Dakota McFadzean is a Canadian cartoonist who has been published by MAD Magazine, The New Yorker, The Best American Comics and Funny or Die. He has also worked as a storyboard artist for DreamWorks, and is an alumni of The Center for Cartoon Studies. To Know You’re Alive is McFadzean’s third book with Conundrum Press. Other titles include Other Stories and the Horse You Rode in On and Don’t Get Eaten by Anything, which collects three years of daily comic strips. McFadzean currently lives in Toronto with his wife and two sons.

To Know You’re Alive is a brilliantly dark collection that offers a glimpse into the cracks between childhood imagination and the disappointing harshness of adulthood. Populated by cruel bullies, exhausted parents and relentless cartoon mascots, McFadzean’s latest work renders the familiar into something that is alien and absurd. The characters in these stories long to uncover something uncanny in shadowy attics and beneath masks, only to discover that sometimes it’s worse to find nothing at all. Get your copy here.

Dr. Norma Dunning is a writer as well as a scholar, researcher, professor and grandmother. Her first book, the short story collection Annie Muktuk and Other Stories, received the Danuta Gleed Literary Award, the Howard O’Hagan Award for Short Story and the Bronze for short stories in the Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Awards. She is also the author of Eskimo Pie, a collection of poetry and an Alberta bestseller. Tainna: The Unseen Ones (Douglas & McIntyre) is an honouring to all Inuit who live outside of their land claims areas and who face modern-day life with humour and tenacity, and with the strength of the giants they are. Dunning lives in Edmonton, AB.

Drawing on both lived experience and cultural memory, Norma Dunning brings together six powerful new short stories centred on modern-day Inuk characters in Tainna. Ranging from homeless to extravagantly wealthy, from spiritual to jaded, young to elderly, and even from alive to deceased, Dunning’s characters are united by shared feelings of alienation, displacement and loneliness resulting from their experiences in southern Canada. There, they must rely on their wits, artistic talent, senses of humour and spirituality for survival; and there, too, they find solace in shining moments of reconnection with their families and communities. Get your copy here.

1:01pm

Saturday, April 20