Founder

Founded by Dessa Bayrock, who used to fold and unfold paper for a living at Library and Archives Canada, and is currently a PhD student in English, where she continues to fold and unfold paper. Her work has appeared in Funicular, PRISM, and Poetry Is Dead, among others, and her work was recently shortlisted for the Metatron Prize for Rising Authors. She is the editor of post ghost press. You can find her, or at least more about her, at dessabayrock.com, or on Twitter at @yodessa.

Tell us a bit about your press. How did you start? Who are your influences, in Canada and beyond? What is your mission?

I founded post ghost press in the summer of 2018 in the twilight of July and the cusp of August. The inception of the press came from a couple of different places: after picking up a handful of poetry zines in Shelf Life Books while visiting Calgary, I became entranced with the one-sheet, eight-page zine style that folds against and into itself to make a tiny book. I was entranced with how I carried this zine with me, pocket-sized, and how easily it could be mailed, this palm-sized poem book, to anyone at all. I began cutting up a series of old science encylcopedias I found in my apartment building’s laundry room and collaged a small story of my own into a zine, and then immediately thought: okay, but how can I start publishing other writers? Two years later I’m still cutting up those encyclopedias, as well as a stack of 70s National Geographics, and mailing these weird little microchapbooks all over the world. It’s a dream – a strange and compelling dream.

What about small press publishing is particularly exciting to you right now?

The small press publishing scene is exciting to me because it feels like such a welcoming space; barriers to entry are relatively few for zinesters and chapbook makers, especially with the advent and blossoming of the online and digital zine community. In an era when time seems to be moving more quickly than ever before, I think these kinds of small books and zines are particularly cogent in the way that they can be picked up and read quickly, or mulled over for much longer if and when the urge takes you. Zines feel like a gathering of kindred spirits to me, an effect compounded by the contrast in big box publishing right now; on one hand, you have these small efforts at community engagement, books or chapbooks or zines that have incredibly small runs and get passed from person to person like talismans, and on the other hand we have a landscape of multinational publishing conglomerates becoming ever more frenzied in search of the next big bestseller. Small press moves at a different pace, a more intimate and thoughtful pace, where connections are drawn between a lot fewer people, sure, but those connections are so much stronger than what you might find in the larger publishing community.

How does your press work to engage with your immediate literary community, and community at large?

I’ve always been a bit of a hermit, so the “immediate literary community”, for me, has never been purely geographical. Instead, the immediate literary community is on Twitter, or in the blogosphere, in addition to being in the cosy barrooms where poetry readings take place in Ottawa. I live down the street from the Manx, which is an amazing and welcoming space for poetry events and so on in Ottawa, and I love sliding into its basement full of copper tables for an evening of quiet comradery. But I also love tweeting and emailing with folks all over the globe, and publishing folks not only from Ottawa (like Conyer Clayton, a local-to-me poet who I deeply admire, for example) but also from Africa, the USA, Australia, Belgium. And I end up sending books all over the world, too – there’s an amazingly supportive reader in Austria who I’ve never met, but who nevertheless purchases just about everything I make. I’ve always loved sending mail, physical mail, and this joy really compounds for me – imagining friends and strangers alike opening their mailbox and finding an envelope full of colour, life, and poetry. Isn’t that nice? Isn’t that a wonderful feeling, imagining that? That’s the community I want to build – one that might be separated by distance and time, but which nevertheless sends out these optimistic tendrils to loved ones.

Tell us about three of your publications. What makes them special, needed, and/or unique?

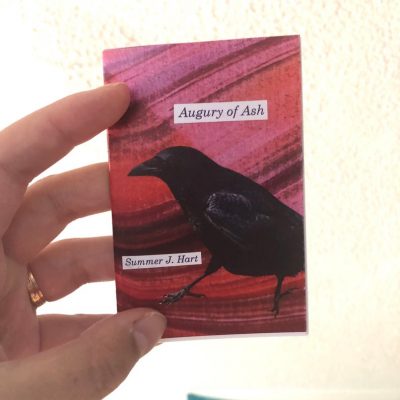

Augury of Ash by Summer J. Hart is one of our newest little books, and I knew as soon as I read the manuscript in our last submissions period that I wanted to publish it. It’s a little dark, in the way that old fairy tales are dark, and it doesn’t necessarily give the reader light at the end of it. All the same, I think there’s something like hope threading through the entire poem – this gossamer filament patched into the ash and soot and wariness of the text itself.

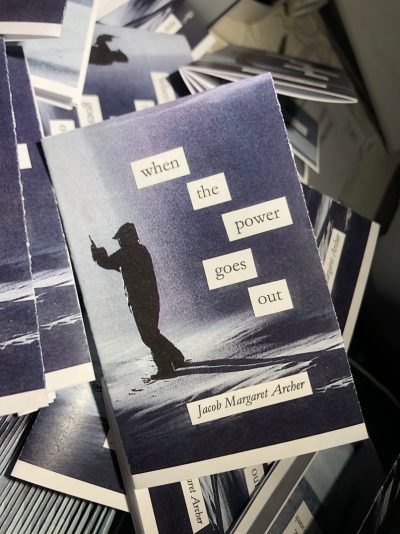

When the Power Goes Out by Jacob Margaret Archer is an eerily prescient creative nonfiction piece which thinks about apocalypse, about the end of the world, and about how even in the most desperate times we will be able and driven to seek out the ones we love. This piece was written in the fall of 2018, and slotted into our publication schedule in late 2019, and was somehow published exactly as COVID-19 laid all our collective plans to waste. What terrible, beautiful, prescient timing. I wish it didn’t have such an illuminated relevance to our lives, but I also think it’s one of the most beautiful – and again, strangely hopeful, and strangely comforting – things I’ve read in my time running this press.

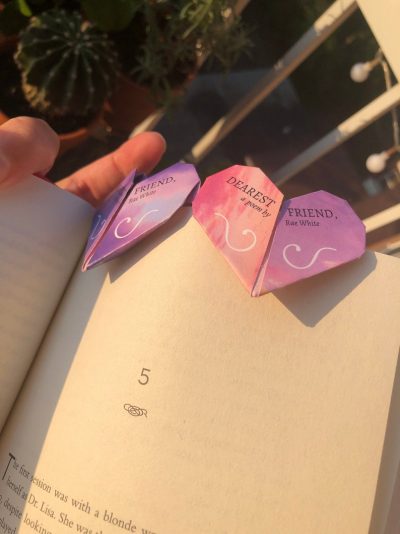

Dearest Friend, by Rae White, is a poem hidden within an origami bookmark; it’s shaped like a heart, and has a sky-filled background coloured in pinks and blues and lavenders. I have several extremely close friendships that are very dear to me, despite the geographic distance between us; I wanted to encapsulate that feeling in a bookmark I could send to my pals, and that other folks could send to their pals. It’s a message of comfort and love and hope, and, above all, connection. It’s so easy to feel disconnected right now, whether we’re alienated against our will (by the technology or physical distance between us, or from issues such as systemic racism and catastrophic climate change due to our individual inability to do much about them) or whether we’re disconnecting on purpose as a kind of self care. I wanted to create something that would remind us that connection is vital between us and our communities; Rae’s poem speaks beautifully to this.

How have the current multiple global crises impacted your work with the press?

Just before the pandemic – and the resurgence of the largest civil rights movement of our time in Black Lives Matter — I’d been collecting submissions for a tiny anthology about love. This submissions stack turned out to be a beautiful resource of hope: all these strangers talking about what it means to love someone far away, to love someone who doesn’t know, to be told they shouldn’t write about love, to be told love doesn’t exist, to love a sister, a mother, a brother, a roommate, a cat. I sat inside my apartment and sobbed over these submissions – these tiny transmissions from the past that spoke so well to the future.

I ended up producing the love anthology, as well as an origami broadside (which was an amazingly fun project, and which I’m so glad I never have to do again and yet can’t wait to try again), and then kept diving into that submissions pile to create another tiny anthology about hope and spring just as we realized that the pandemic was going to stretch into the spring, and summer, and god knows how much else longer. I have a third anthology, too, lined up from this submissions stack, and I think its time is coming closer, since this collection is less about love and hope and more about what the world looks like after positivity has waned: a reminder that anger, bitterness, and bad dreams are blossoms and fruits of the same plant, and that they also deserve to be heard.

Augury of Ash

Summer J. Hart

August 2020

Augury of Ash is one of our newest little books, and I knew as soon as I read the manuscript in our last submissions period that I wanted to publish it. It’s a little dark, in the way that old fairy tales are dark, and it doesn’t necessarily give the reader light at the end of it. All the same, I think there’s something like hope threading through the entire poem – this gossamer filament patched into the ash and soot and wariness of the text itself.

When the Power Goes Out

Jacob Margaret Archer

April 2020

When the Power Goes Out is an eerily prescient creative nonfiction piece which thinks about apocalypse, about the end of the world, and about how even in the most desperate times we will be able and driven to seek out the ones we love. This piece was written in the fall of 2018, and slotted into our publication schedule in late 2019, and was somehow published exactly as COVID-19 laid all our collective plans to waste. What terrible, beautiful, prescient timing. I wish it didn’t have such an illuminated relevance to our lives, but I also think it’s one of the most beautiful – and again, strangely hopeful, and strangely comforting – things I’ve read in my time running this press.

Dearest Friend (an origami poem)

Rae White

May 2020

Dearest Friend is a poem hidden within an origami bookmark; it’s shaped like a heart, and has a sky-filled background coloured in pinks and blues and lavenders. I have several extremely close friendships that are very dear to me, despite the geographic distance between us; I wanted to encapsulate that feeling in a bookmark I could send to my pals, and that other folks could send to their pals. It’s a message of comfort and love and hope, and, above all, connection. It’s so easy to feel disconnected right now, whether we’re alienated against our will (by the technology or physical distance between us, or from issues such as systemic racism and catastrophic climate change due to our individual inability to do much about them) or whether we’re disconnecting on purpose as a kind of self care. I wanted to create something that would remind us that connection is vital between us and our communities; Rae’s poem speaks beautifully to this.